Success stories in instructional coaching often feel personal. They grow from the needs and goals of fully dimensional people. One teacher’s classroom goals may be completely different from another’s and require different strategies. Administrators and educational leaders face new and unique challenges as they support coaching programs in their schools. And – most importantly – each student has their own unique needs to learn.

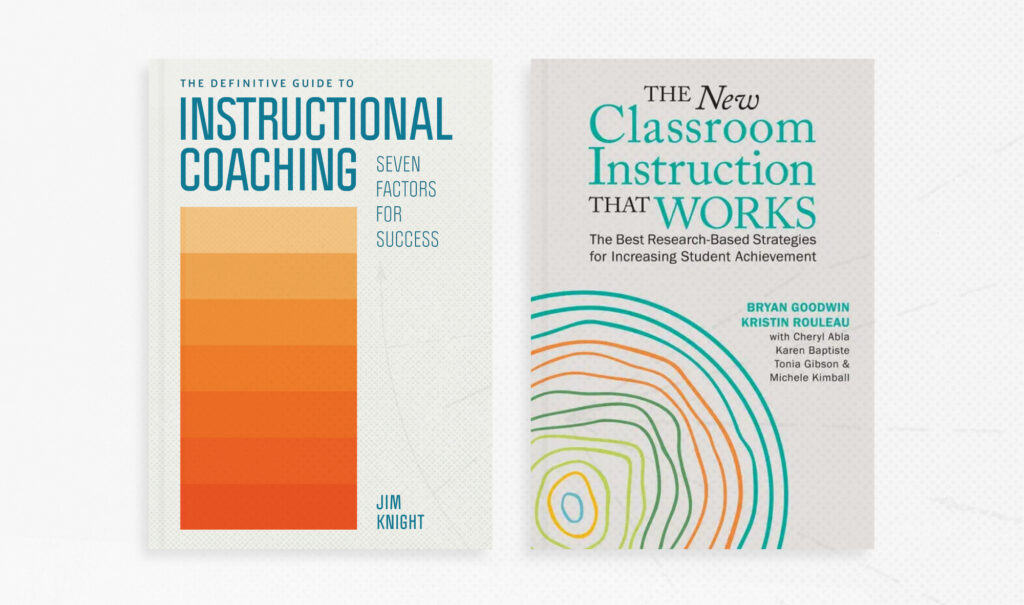

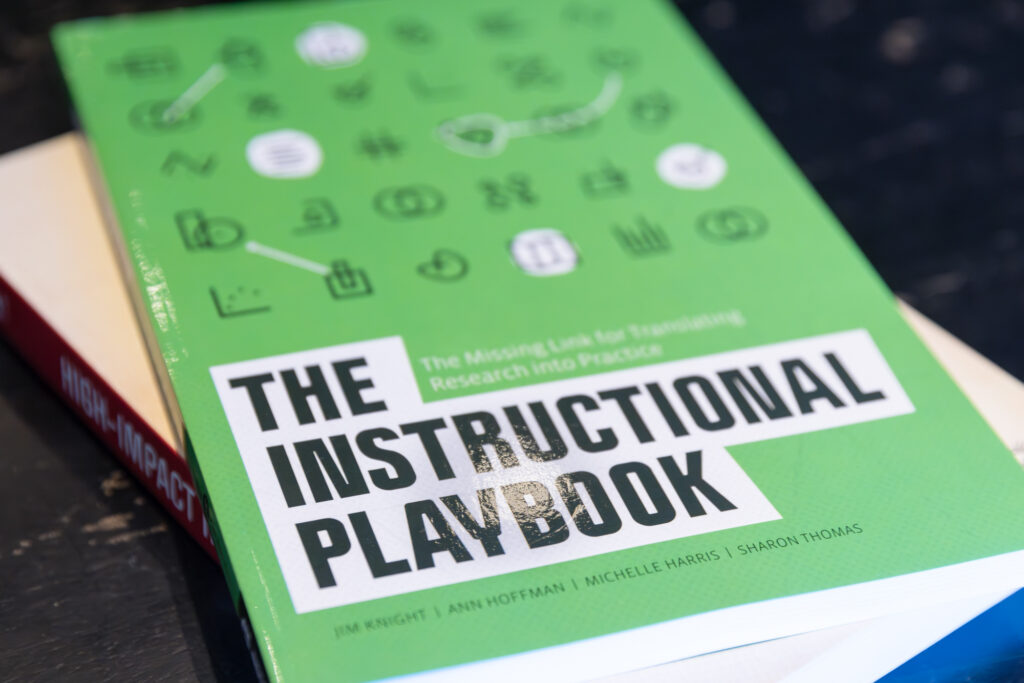

Though decades of research have led to profoundly impactful professional learning opportunities for instructional coaching, there has never been one concise, definitive text for any educator to apply to their coaching program. Now there is.

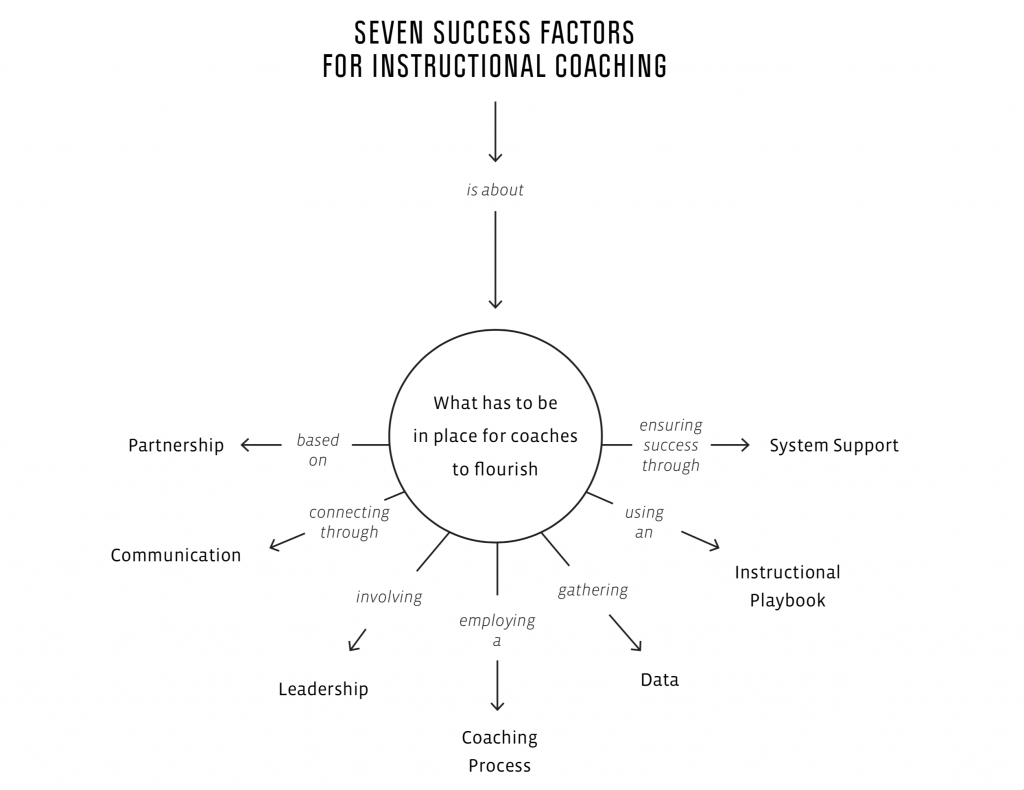

Created by identifying common factors in successful coaching programs from all over the world, The Definitive Guide to Instructional Coaching: Seven Factors for Success by Jim Knight offers a blueprint for establishing, administering, and assessing an instructional coaching program laser-focused on every educator’s ultimate goal: the academic success of students.

A partnership approach is cruical to the success of a coaching relationship, and in order to encourage this way-of-being, Jim Knight developed the Partnership Principles. The following excerpt from from Chapter One: The Partnership Principles begins with the principle of choice:

The way coaches interact with others frequently determines whether their coaching is successful. If coaches see themselves as superior to others, they may find that others are not interested in hearing what they have to say. As M.I.T. organizational development specialist Edgar Schein (2009, 2013, 2018) has explained, people often resist ideas shared with them if they perceive that the status they think they deserve is not being acknowledged.

Carl Rogers first popularized the phrase “way of being” in his 1980 book of the same name. Put simply, “way of being ” refers to how we are in the world with others, including whichever set of principles we live by. (And whether we realize it or not, every one of us lives according to a set of principles.) The Partnership Principles form one such set that can serve as a foundation for mutually humanizing learning conversations. One important principle is choice:

Choice

When coaches embrace the principle of choice, teachers make most, if not all, of the decisions about changes to their classrooms. There is freedom in the conversation that isn’t possible when coaches try to control what teachers do. When a conversation feels “off ” or “out of sync,” it is often because collaborating teachers don’t feel they are free to say, do, or think what is on their minds.

What the research says about choice

Working from the principle of choice is not just a nice thing to do, but a practical necessity. More than three decades of research has shown that telling professionals what to do without giving them a choice almost always results in failure. Researchers such as Teresa Amabile and colleagues (1996), Richard Ryan and Edward Deci (2017), and Martin Seligman (2012) all consider autonomy to be essential for motivation. Ryan and Deci characterize the conclusions they’ve drawn from decades of research as social determination theory—namely, the idea that people feel motivated when they (1) are competent at what they do, (2) have a large measure of control over their lives, and (3) are engaged in and experience positive relationships. The theory posits that the opposite is also true: When people are controlled and told what to do, are not in situations where they can increase their competence, and are not experiencing positive relationships, their motivation will be “crushed” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 68).

A report from the Institute of Educational Sciences (Malkus & Sparks, 2012) summarizes research showing the importance of teacher autonomy:

Research finds that teacher autonomy is positively associated with teachers’ job satisfaction and teacher retention (Guarino, Santibañez, and Daley 2006; Ingersoll and May 2012). Teachers who perceive that they have less autonomy are more likely to leave their positions, either by moving from one school to another or leaving the profession altogether (Berry, Smylie, and Fuller 2008; Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, and Wyckoff 2008; Ingersoll 2006; Ingersoll and May 2012). (p. 2)

Yet despite the important role of choice, research suggests that autonomy is decreasing for almost all teachers (Malkus & Sparks, 2012).

Why choice is important

Choice is essential for at least three reasons. First, top-down models of change usually do not work. Telling professionals what they have to do might yield compliance, but not commitment (Deci & Flaste, 1996). Many educators have experienced top-down initiatives that were rolled out with a lot of fanfare but wound up having little impact on how teachers teach and how students learn.

Second, controlling other people is dehumanizing. As Donald Miller has written, “the opposite of love is . . . control” (2015). Our ability to make choices largely defines our humanity. When we tell people they have no choice, we take away their ability to choose to commit—and, more important, to think for themselves. “Saying no is the fundamental way we have of differentiating ourselves,” writes Peter Block. “If we cannot say no, then saying yes has no meaning” (1993, p. 29).

Finally, choice is essential for accountability. We might think that accountability refers to people doing what they are told, but I refer to this as irresponsible accountability because it leaves out the crucial factor of personal responsibility. A few years back, at our intensive coaching institute in Kansas, one instructional coach painted a vivid picture of what irresponsible accountability can look like in our schools: “Our principal went to a teacher to talk about her students’ low achievement scores,” she said. “When the principal raised the topic of the scores, the teacher pointed out that she was implementing the program the district had told her to implement. ‘I did everything I was told to do, and I did it with fidelity,’ she said. ‘If my students aren’t doing well, I’m not the problem—it’s your program.’”

Responsible accountability is different. When educators are responsibly accountable, their professional learning has an unmistakable impact on student learning, making them accountable to students, parents, fellow educators, and other stakeholders. Further, at the individual or school level, responsible accountability represents a genuine commitment, both individually and collectively, to professional learning and growth—a recognition that, to have learning students, we need to also have learning teachers, learning coaches, and learning administrators. In short, responsible accountability is essential for professional learning—and it isn’t possible without choice.

What choice is not

Research suggests that choice is essential, but that’s not the same as saying “anything goes.” Choice does not mean that teachers can bully students, lose assignments, or be toxic members of a team. Choice also does not mean that teachers can choose to ignore district initiatives, skip over non-negotiables, or stop learning. Choice need not lead to incoherence, either. Indeed, true coherence requires commitment, and commitment requires choice. There will be better implementation and deeper commitment to coherence when teachers have an authentic voice in making the decisions that most matter to them.

Instructional coaching done well produces measurable improvements that lead to better learning and better lives for students. It also ensures that teachers set their own goals, choose the strategies they’ll use to meet those goals, monitor progress, and determine for themselves when their goals have been met. Further, coaches honor teacher autonomy by ensuring that teachers’ voices are heard.