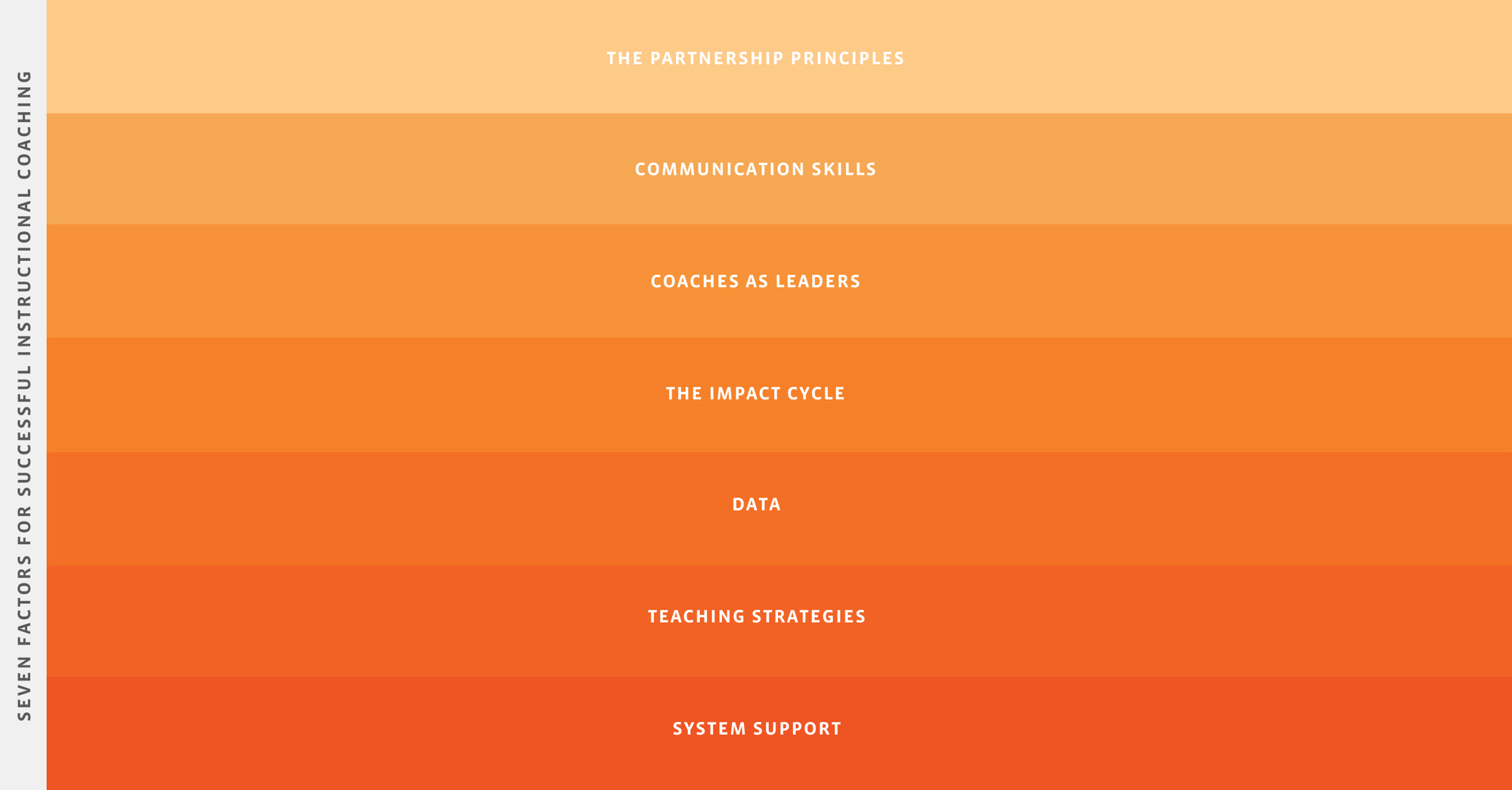

Over the next 7 weeks, the Radical Learners blog will examine Jim Knight’s 7 Success Factors for Effective Coaching Programs. These success factors (grounded in more than 20 years of research) are also the frame for ICG’s certification program for instructional coaches. That program is the only instructional coaching certification that requires evidence of daily coaching practice that meets research-based criteria for excellence. Whether you’re a system leader or school-based administrator who wants more information on how to evaluate the impact of coaching or a coach interested in becoming ICG certified, these blogs are for you.

Success Factor 1: The Impact Cycle

The cornerstone of Jim Knight’s work in schools is the Impact Cycle. The Impact Cycle (our research-based take on the more general term of “coaching cycle”) distinguishes itself among other definitions of that cycle in several ways:

- its foundation in the research on adult learning and how adults react best to change

- its focus on the teacher as the key decision-maker in the improvement process

- its specific tools (such as its use of video and multiple sources of data, the Identify Questions, the Instructional Playbook, the Improve Questions, etc.) to ensure partnership and follow-up throughout the process

The Impact Cycle Defined

Simply put, the Impact Cycle is a voluntary process through which teachers request coaching support on a goal they have for their students, and the coach provides as much data gathering, modeling, checklists, and follow-up support as the teacher wants in hitting the goal and in the implementation of the strategy the teacher chooses to hit the goal.

In our experience, coaching programs usually come about quickly due to an identified need for teacher support generally or in a particular area of student underachievement. Coaching positions are then created but without a philosophical and/or research rationale driving the job description. Thus, the many definitions of how “coaching” is perceived are all in play among the stakeholders involved, and the new coach begins work receiving conflicting messages about what exactly they are supposed to do and what coaching looks like. This lack of role clarity then spirals over time into a perception of the coach having more “free time” than other educators in the building because no one is sure of exactly what the coach does or should be doing.

That extra-time misperception leads administrators to load up the coach’s day with “other duties as assigned” (standardized test coordinator, pull-out interventionist, halllunchbus duties, etc.). In short order, the coach is so occupied with quasi-administrative roles that he or she has little time to work on goals with teachers in classrooms.

Those quasi-administrative roles not only have no research base saying they move kids forward (unlike the Impact Cycle, which does), but also those roles position the coach as “one-up” in status in the school and thus make teachers less likely to want to be coached because the coach is perceived as a quasi-administrator (and thus evaluative).

To ensure that coaches have more impact on student success, freeing up as much time for them as possible to work in classrooms with teachers on student-focused goals is critical. That Impact Cycle process has three phases:

- Identify: In this stage, the coach and teacher collect data to help the teacher set a goal that is powerful for students and compelling for the teacher and select a strategy to help the teacher hit the goal.

- Learn: Once the teacher has chosen the goal and the strategy, the coach helps the teacher learn the strategy deeply through modeling and the use of checklists (both at the discretion of the teacher) so that the teacher feels supported during the implementation of something new.

- Improve: In this stage, the teacher and coach continually revisit progress on the goal and make any changes to the goal or to the strategy as progress warrants.

Throughout the Impact Cycle, the teacher is the designated decision-maker, but the coach engages in dialogue with the teacher so that both educators’ expertise is part of the conversation.

ICG Certification: What Scoring Taught Us This Year

Over this past summer, we scored our first set of portfolio entries from our pilot cohort in our new certification process. That scoring process not only helps us to clarify the candidate directions and portfolio entry descriptions, but also it helped us to see where misconceptions exist regarding the implementation of the Impact Cycle itself.

The primary misconception with some of the first Impact Cycle entries we scored this year involves the difference between “instructional coaching” as we define it and “technical support.” Jim wrote a blog on this topic recently, and it is a distinction that our workshop participants wrestle with a great deal. Long story short, instructional coaching involves a teacher choosing his or her own goal, choosing his or her own strategy to hit the goal, and choosing whether or not to be coached in the first place. The choices for the teacher in these areas may be limited and among a menu of options for teachers in a given system, but choice is key. Coaches support the teacher as a partner throughout the work on the goal.Technical support, on the other hand, involves a support person (often labeled a “coach”) whose job is to support or enlist teachers in an implementation of a strategy or program that a system or school has chosen to hit a school- or system-selected goal. Teachers don’t have much choice (or, often, any choice) in implementing that program, and the term “coach” may be in play to try to make teachers feel that the process is less compulsory than it is.

Many coaches are hired as technical support for an initiative, but when they learn more about how to best engage teachers in change and improvement, they want to engage more as partners and offer choices, as in the Impact Cycle. These desired roles changes should involve important conversations with school and system leadership about which coaching models have the strongest research base (including close scrutiny of that research) and which model is most likely to engage more teachers in it.

To fully implement the Impact Cycle means that teachers are treated as professionals who have choices. They do not have the choice not to improve (all professionals, by definition, are constantly improving), but they do have the ability to choose what, when, how, and with whom to improve to at least some degree.

School and system leaders who want to “move the needle” on student success need to wrestle with which kind of support is best for their schools. The Impact Cycle research shows that an emphasis on a partnership model that respects teachers as knowledgeable and capable can move the needle not only on student achievement measures but also can move the needle on school culture as a whole.